Your Most FAQ About Strongyles in Horses, Answered

by: John Byrd, DVM, Horsemen’s Laboratory

Strongyles are the most common parasite found in horses. Approximately 33% of the samples that are examined by Horsemen’s Laboratory are positive for worm eggs. Over 95% of those positive samples are due to strongyle eggs.

The two most frequently asked question concerning strongyles are:

Are the eggs from large or small strongyles?

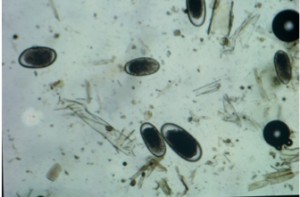

The eggs from large and small strongyles appear very similar and cannot be differentiated. The eggs must hatch and then the larvae can be identified as large or small. Research has shown that eggs found today in most situations are 95% small strongyles because Ivermectin use has nearly eliminated the large strongyles.

Do you only check for strongyles?

Horsemen’s Laboratory looks for other worm eggs, but seldom finds any; this may be due to fact that over 80% of our horses are adults over 4 years of age. If they are found they are certainly reported.

Since strongyle eggs are so much more prevalent, I will discuss some of the characteristics of them.

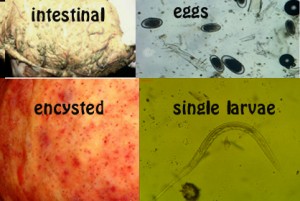

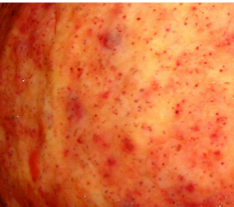

Eggs produced by adult female strongyles and passed in the stool of a horse. Photo provided by Horsemen’s Laboratory.

Large strongyles are also known as bloodworms, red worms or migrating strongyles. These common names come from the characteristics of the adult worms. There are three species of large strongyles: Strongylus equinus, edentatus and vulgaris. All strongyles have a very similar beginning to life. The adult females lay eggs that are mixed and passed with the horse’s stool. Once passed with the stool, the eggs hatch and develop into infective stage larvae in three to seven days under favorable conditions.

Infective strongyle larvae in a drop of dew on a blade of grass. Photo courtesy of Horsemen’s Laboratory.

The infective larvae crawl from the pile of stool and up on blades of grass in order to be eaten so that they can get in to the large intestine. Each take a different path in migrating through the horse’s internal organs. During this time, it is developing into the later larval stages on its way to becoming an adult. All three penetrate the wall of the intestine and then migrate through the liver and pancreas eventually into the blood stream.

Once in the blood stream, equinus and edentatus travel back to the intestinal wall, burrow through, become adults, suck blood, and start laying eggs. Vulgaris, on the other hand, enters the blood stream and seems to congregate in the cranial mesenteric artery (the artery supplying the anterior portion of the intestine) there it causes severe damage to the lining of the vessel. If the damage is severe enough, it can cause the artery wall to weaken and rupture or blood clods and scar tissue to form (thrombus).

When these blood clods break off, they become known as emboli. These blood clods then may become lodged in the smaller arteries causing a blockage of blood flow to a section of intestine. Since there is no blood flowing to a section of the intestine, the body tries to revascularize that section if it is not too large. However, if it is a large area of intestine that is affected, it will die causing the intestine to rupture. This process is termed thrombi-embolic colic, sometimes necrotizing.

This process frequently occurred before Ivermectin was available. Ivermectin was the first dewormer that was actually absorbed from the intestine at a high enough level in the blood stream to kill the larvae and prevent this damage from occurring. After the larvae do all this damage, they travel with the blood flow to the intestine, burrow back into the intestine, become adults, suck onto the intestinal wall, start sucking blood, and laying eggs. When these adults are engorged with blood, they are very red giving rise to the other two common names of bloodworms or red worms. Before Ivermectin, large strongyles were by far the most pathogenic (destructive) parasite of horses often causing colic and anemia. Ivermectin has been credited with greatly reducing the number of large strongyle infections we now see. Recent surveys done indicate only about 5% of strongyle eggs found are from large strongyles.

Small strongyles (cyathostomes), non-migratory strongyles, have now taken over as the most common intestinal parasite of horses. There are over 40 species of small strongyles. As previously stated, 95% of the positive tests at Horsemen’s Laboratory are due to strongyle eggs. The surveys indicate that 95% of those eggs are likely from small strongyles. These eggs are produced by adult small strongyle females generally 1-inch in length or less and are passed in the stool of horses.

These eggs hatch and go through a three stage larval development to the infective stage in three to seven days under favorable conditions. The infective larvae crawl from the pile of stool and up on blades of grass in order to be eaten so they can get in to the large intestine and penetrate the mucosal lining of the intestine where they become encysted and they remain for two weeks or more, sometimes up to two years or more. The larvae continue to develop in the cysts where they are well protected from most dewormers at normal doses.

Encysted strongyle larvae in intestinal mucosa. Photo Credit: Dr Martin K. Nielsen at the University of Kentucky.

Every encysted larva had to, at one time, be an egg that is passed in a horse’s stool, which brings me to another topic that I would like to address. Often we hear that by doing stool samples, you cannot tell if your horse has encysted strongyles. I would agree if you only do one stool sample. However, if you do stool samples periodically on the horses in a pasture and establish that they are passing large numbers of eggs then it follows that there are large numbers of infective larvae in that pasture for the horses in that pasture to consume. This would then suggest it is likely there will be many more encysted larvae in those horses than in horses in a pasture where very few eggs are being passed.

This leads to another reason we recommend doing stool samples. It has been established that horses may be classified as low, medium, and high shedders of strongyle eggs. Once it is known which group a horse falls into, it generally stays in that group unless something changes drastically in its environment. An owner has a couple of options once their horses’ egg shedding class is determined to better control strongyles. First, you may deworm the horses more often that are the major egg shedders. Secondly, you may want to divide the pasture and separate the horses according to their egg shedding rate thereby limiting the number of horses that are exposed to high number of infective larvae.

It has been stated that 20% or less of the horses in a pasture are passing 80% of the strongyle eggs. This fact has certainly been found to be true in the samples we receive at Horsemen’s Laboratory. We often receive samples from several horses that are in a pasture together with one or two horses having 2000 – 4000 eggs/gm while others in the same pasture may only have no eggs or very low counts of 100 – 200 eggs/gm.

In this article I have tried to touch on some of the most frequently asked questions by our clients here at Horsemen’s Laboratory concerning strongyles in horses. If you have other questions please feel free to contact me directly.

If you have questions specific to your barn, pastures, or testing program contact Dr. John Byrd by:

· E-mail: hlab@horsemenslab.com

· Phone: (800) 544-0599

· Contact form: www.horsemenslab.com

To order testing kits visit: www.horsemenslab.com or call: (800) 544-0599.

Horsemen’s Laboratory owner, Dr. John Byrd, has extensive experience with racing and breeding horses and maintains Westbrook Boarding Stable. He founded Horsemen’s Laboratory in 1992 so that horse owners could better evaluate their worm control programs and make informed decisions about deworming their horses. Visit www.horsemenslab.com to learn more about Horsemen’s Laboratory and parasites, to sign up for the monthly newsletter, and to order testing kits.