Hot Weather and Equines

By Brian S. Burks, DVM, Diplomate, ABVP, Board Certified in Equine Practice

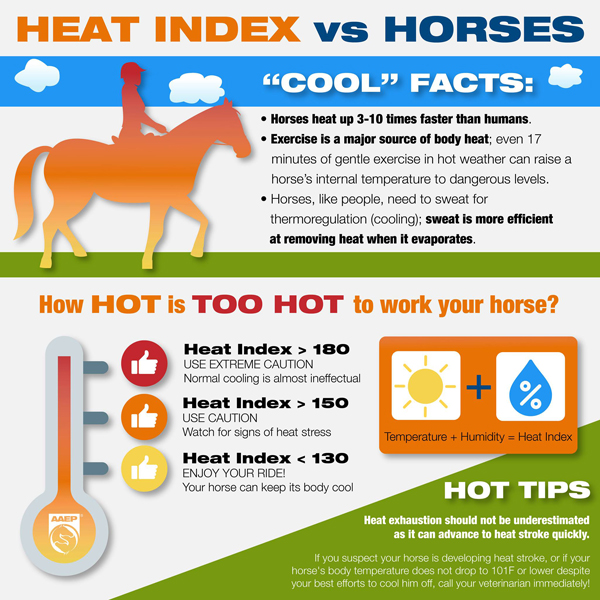

Horse owners need to consider management practices for horses during hot and especially hot and humid weather. When horses exercise, heat is generated, elevating the body temperature. There are mechanisms in place to allow dissipation of heat, mainly sweating, but also superficial vasculature dilatation. Sweating allows heat removal via evaporation, but when humid conditions occur with extremely hot temperatures, the sweat cannot evaporate, and heat dissipation is compromised. The same is true of vasculature dilatation; although the superficial blood vessels dilate and more hot blood is brought to the surface, hot temperatures prevent heat loss- heat from the body needs cooler temperatures outside for heat loss to occur.

When the sum of outside temperature plus the relative humidity is below 130 (e.g., 70 F with 50% humidity), most horses can keep their body cool, with the exception will be very muscular or fat horses. When the sun temperature and humidity exceed 150 (e.g., 85 F and 90% humidity), it is hard for a horse to keep cool. If the humidity contributes over half of the 150, it compromises the horse’s ability to sweat – a major cooling mechanism.

When the combination of temperature and humidity exceeds 180 (e.g., 95 F and 90% humidity), the horse’s cooling system is almost ineffectual. At this stage, exercise can only be maintained for a short time without the animal’s body temperature— especially in the muscles— rising to dangerous levels. Little cooling takes place even if the horse is sweating profusely. When the horse’s body temperature reaches 105 F, the blood supply to the muscles begin to shut down. After this occurs, the blood supply to the intestines and kidneys also shut down. The blood supply to the brain and heart are spared until last, but severe and permanent damage may have already taken place.

Signs of heatstroke may include the following:

1). Temperature as high as 103 to 107 F

2). Rapid breathing, rapid pulse

3). Stumbling, weakness, depression

4). Refusal to eat or work.

5). Dry skin and dehydration

6). With severe cases, a horse may collapse or go into convulsions or a coma

Horse owners can help their horses cool by employing four management practices. These include good ventilation, encouraging water intake, carefully planned exercise, and actively observing for signs of heat stress. One way to help horses get through hot weather is to ensure that barns are adequately ventilated. This can be done by opening doors and windows. Fans can also be used to increase air flow. A fan over each stall will move air directly over the horse. Fans with mist attachments can also be used but may not provide any additional benefit to a regular fan in humid areas.

Assuring adequate water intake is critical. On average a 1,000 lb. horse needs 8 to 10 gallons of fresh water per day. As the air temperature increases, even horses at rest sweat and consume more water. When temperatures exceed 70 F, adult horses may consume 20 to 25 gallons of water per day; exercising horses will consume up to double this amount. An owner can encourage the horse to drink water by providing salt blocks or loose salt in the feed. Horses should be offered fresh water frequently and have access to water at all times. It is also advisable to offer an additional bucket containing commercially available horse electrolyte solutions mixed with water; however, the provision of plain, fresh water is always required when electrolyte water is offered. This can be beneficial especially if the horse is losing electrolytes through sweating; however, some horses will not willingly drink electrolyte solutions mixed with water so an alternative water source should be made available. An additional management practice to decrease heat stress is avoiding exercise during the hottest time of the day, typically from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Turn horses out to pasture at night, especially if the pasture is lacking shade.

Notify your veterinarian immediately if any signs of heat stroke are observed. Before your veterinarian arrives, owners should provide frequent small amounts of cool water for the horse to drink. Electrolytes may also be given orally. If possible, stand the horse in the shade and/or in front of a fan. To cool the body, ice, or cold hose the major blood vessels. The vessels that should be iced are the jugular veins, the major veins that run down both sides of the neck, the veins on the inside of the front of the legs and the large veins on the inside the back legs. Ice packs or cold water from a hose will cool down the blood as it circulates through the body. It acts as the “antifreeze” and cooling system as it circulates. Avoid icing the large major muscles of the loin and hind end. These muscles are already lacking blood circulation and may make the condition worse due to vascular constriction. Icing the forehead helps to cool the horse since the brain contains the temperature control center for the body. In severe cases, intravenous fluid therapy is necessary to treat dehydration, electrolyte loss and shock. Alcohol baths (isopropyl) can also be helpful to lower elevated body temperatures.

When using water to cool a horse, heat is escaping by convection, which means the water will heat up quickly, and can worsen the overheating. Continuous cold water should be used to remove the heated water. This will cool the horse quickly. The application of very cold water in this manner will not cause muscle cramping because it is not in contact with the body long enough.

Once you have initiated first-aid, continue to take, and record, the horse’s rectal temperature every 15 minutes until the veterinarian arrives. In severe cases it may be necessary for your veterinarian to administer intravenous fluids to combat dehydration and electrolyte imbalances associated with heat exhaustion. Your veterinarian also will consider the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as flunixin meglumine or phenylbutazone to aid in patient well-being and to aid in the reduction of elevated body temperature.

In summary, owners should understand what they can do to avoid heat stress in their horses and to recognize the signs of heat stress so that prompt veterinary care can be provided when necessary.