Foot Fractures

Click here to read the complete article

by Heather Smith Thomas

There are three bones inside the horse’s foot—the coffin bone (3rd phalanx), the lower end of the short pastern bone (2nd phalanx) that attaches to the coffin bone, and the small navicular bone that sits behind the coffin bone. These bones articulate together in the coffin joint. Of these three bones, the one most commonly fractured is the coffin bone.

CAUSES

Nathaniel A. White, DVM, MS, DACVS (Professor of Surgery, Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center) says it’s hard to predict what causes a coffin bone to break. “The foot might land with excessive impact on an uneven surface. A rear foot might suffer a fracture if the horse kicks a concrete wall,” he says.

Alicia L. Bertone, DVM, PhD, Diplomate AMCVS (Trueman Family Endowed Chair and Professor at The Ohio State University) says the primary cause of any fracture in the foot is some sort of hard landing. “This could be excessive impact such as landing on a rock, jumping and coming down hard, perhaps with a twist. It’s typically a high-impact injury. This can happen in racing, jumping, or even on a longeline,” she says.

“The fracture usually occurs during exercise or galloping in a pasture. The foot suffers enough impact, with enough force, that it breaks the bone. The hoof capsule is designed to protect it; the outside horn is hard and immobile, though it can expand and contract at the heels and the sole is tough and resilient. The hoof capsule protects the bones, but not completely,” she explains.

There are certain risk factors for various coffin bone fractures. “The coffin bone looks somewhat like a horseshoe. Toward the back, one of the ‘wings’ may fracture off. This is often a racehorse injury, but may occur in a horse galloping around a pasture, hitting something hard. It can occur in top-level performance horses, such as sport horses,” says Bertone.

“Coffin bone fractures occur in all kinds of horses,” says White. “It might be a stress-type fracture in exercising horses (from cumulative stress due to speed and repetitive impact rather than a one-point-in-time impact), and this has been detected in horses diagnosed with MRI,” he says.

DIAGNOSIS

“Fractures that don’t involve the joint can sometimes be a little tricky to diagnose,” says Paul Goodness, Chief of Farrier Services at Virginia Tech’s Equine Medical Center in Leesburg, Virginia. “The horse may be lame, with some heat in the hoof or an increased digital pulse, and the owner suspects a bruise or a nail. The foot may or may not be reactive to hoof testers. If the fracture involves the joint, there may be some coffin joint swelling,” he says.

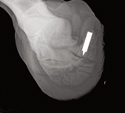

Nerve blocks and radiographs are often used for diagnosis and it may take a combination of these to pinpoint a fracture, since a typical lameness series may not pick them up. “It may take a few oblique views to see the fracture. It is often difficult to see, no matter what angle you are shooting the radiographs. In these cases it helps to use nuclear scintigraphy or MRI, or a CT scan if these modalities are available. Some cases can be determined with a posterior digital nerve block, but an abaxial sesamoid block may be necessary to point the veterinarian in the right direction. A coffin joint block may be needed for a fracture that affects the joint, but these will usually require an abaxial to block it out completely,” says Goodness.

Sometimes a fracture won’t show up on x-rays until 5 to 10 days after the injury. “After osteolysis sets in, this tends to highlight where the crack is located. This is a normal part of the healing process and makes a dark line that is more visible on x-rays,” he says.

“Diagnosing a split down the front of the bone is fairly straightforward,” says Bertone. “These horses will be acutely lame, even at a walk. There will be heat in the foot, an increase in digital pulses to the foot, and the foot will show positive to a hoof tester examination putting pressure on the foot. These tell-tale signs—acute onset, non-weight-bearing lameness, pulse in the foot, and sensitivity to hoof testers—would warrant x-rays. About 80% of the time the diagnosis can be confirmed with an x-ray,” she says.

“Once in a rare while, the crack will be such a fine line that if you don’t get the x-ray view exactly right you might not be able to see it. If it can’t be picked up on x-rays, we recommend that the horse comes back for new x-rays in 30 days. During that time the owner or veterinarian is usually poulticing the foot, hoping it’s just an abscess. If it isn’t, the x-ray will eventually show the fracture,” she explains.

The veterinarian might do a nuclear bone scan, or an MRI, and these imaging modalities could clearly show that there is a fracture. Most people don’t jump right to these diagnostic tools, because these are more expensive and they are still hoping that it’s an abscess. They choose to soak the foot and then x-ray it again later if the pain and lameness doesn’t resolve.

“In any athlete that is sound one day and then comes up lame immediately after exertion, however, you need to be suspicious that it’s a fracture,” she says.

“If a horse doesn’t want to bear weight on a foot and there is pain when applying hoof testers, a radiograph should be taken right away,” says White. “It’s best to do this immediately, rather than after doing any other diagnostic tests such as nerve blocks. If it’s possibly a stress fracture (a small fissure in the bone) that hasn’t sepa-rated yet, we don’t want to do a nerve block and jog the horse—because there is a risk of having the bone separate and become fractured when jogging the horse,” he explains. This is a judgment call by the veterinarian, but when the horse is very lame, and sensitive in the foot, the veterinarian may go right to the radiograph to avoid making it worse.

“MRI is helpful, as well. Now that MRI is available to image the foot, we can detect bone inflammation when there is nothing detected on radiographs (no evidence of a fracture or anything else). If there is potential for a stress fracture, the MRI will show an increase in bone reaction. Fluid in the bone can be detected along the line where the bone is weakened and a fracture might occur. MRI identifies these stress lines before the bone fractures,” he explains.

“In this situation the horse can be rested, and the foot protected with supportive shoeing. These horses respond and heal before the fracture occurs,” says White.

“Nuclear scintigraphy (bone scan) can also help with diagnosis. If there is activity in the region of bone stress—that is not seen on radiographs because it’s still in early stages—this increase in bone metabolism will show up on that scan,” he says.

The primary goals for treatment include immobilizing the bone, reducing inflammation, and limiting the horse’s activity until the fracture heals.

Shoeing/Casting – “If the bone isn’t separated yet, treatment generally consists of support for the foot, using a special shoe such as a bar shoe,” says White. This protects the hoof and keeps it from expanding when weight is placed on it. With a regular shoe, the hoof can flex a bit from side to side, but with a bar shoe this movement is decreased.

“If the fracture goes into the coffin joint—breaking the cartilage at the joint surface and the joint is open—a bar shoe with clips around the hoof is recommended. An alternative is a rim shoe filled with acrylic all the way around the foot. This gives even support around the entire hoof. The goal is to try to stop hoof wall movement and use the hoof as a cast. A fiberglass cast can be applied on the hoof initially, to protect it, but a shoe is used for long-term support,” he says.

Horses with severe fractures are often put in a cast that goes clear up around the pastern, to halt any motion in the coffin joint, according to Bertone. “If it’s an articular fracture, a hoof cast is the ideal choice. In an acute, non-weight-bearing fracture that definitely involves the coffin joint, I generally put the horse in a foot cast for 30 days, followed by a rim shoe with clips,” she says.

For a wing fracture that is just at the joint or debatable whether or not it affects the joint, the horse is usually put into a hoof cast, followed by a shoe with clips. “Putting a screw in those is not helpful. It would be coming in at an angle and it’s difficult to get it right,” says Bertone.

“Instead, we stick to conservative treatment (stall rest and immobilization of the foot in a cast or shoe) and these horses tend to recover and become sound again and usable within about 8 months—which is a bit sooner than for a more severe type of fracture,” she says.

“In our practice we usually use some type of shoe that inhibits any movement and keeps the hoof from expanding,” Goodness says. “One option is a continuous rim shoe, which is like one big long clip around the foot (extending up from the shoe) that starts at one heel quarter and goes around the toe and ends at the other heel quarter. We may also use a bar shoe that has 6 to 8 strategically-placed regular clips to clamp the hoof wall. We also have some high-tech glue-on shoes that are used in conjunction with composite cloth. When you mix adhesive with this, the shoe becomes quite rigid. We’ve successfully used these shoes as hoof casts,” he explains.

A multiple fracture, in which the bone is broken into several pieces, doesn’t have many options for treatment other than putting the foot in a stabilizing shoe to try to support it. “These can heal, but it depends a lot on the amount of joint damage,” says White. If there are several fractures into the joint, this lowers the prognosis for good healing because of the arthritis that is likely to occur in the coffin joint.

Reducing Inflammation – “At the same time, the joint may be treated for inflammation, usually with hyaluronic acid (HA),” says White. “Corticosteroids are not used for the acute fracture because they can inhibit healing in the bone. If the horse is in a lot of pain, anything to make the foot more comfortable is helpful.” This could include using ice daily, along with phenylbutazone or another non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drug such as firocoxib (Equioxx®) to reduce the pain.

Resting the Horse – “The horse should also be rested. Depending on what it looks like on the MRI or scintigraphy, stall rest is the best option, perhaps with a little bit of hand walking. The horse should have very limited activity so you don’t continue to cause a problem. These stress-fracture cracks (that are not yet separated) can take 3 or 4 months to fully heal. The horses may be sound in a month or two, but if exercise is started too soon the horse may create a repetitive problem at that site,” White explains.

It’s better to be conservative, and take more radiographs to see if there are any indications to tell whether it’s healing. “There may not be anything evident on x-rays but the MRI can be repeated to see if the bone activity is decreased. This is the best way to monitor the progress,” says White.

“It’s alright if the horse puts weight on the foot after the acute phase, but exercise should be restricted to absolute stall rest,” he says. Any impact/concussion should be avoided as much as possible.

“If the fracture is an actual break, the horse needs to have stall rest (no exercise). If after two to three months there is no lameness, the foot can be checked with a radiograph to decide if the horse can have turnout. These fractures can take a long time to heal, often requiring a minimum of 6 months. During turnout the foot is kept in a supportive shoe with clips or acrylic support all the way around the hoof wall. Sometimes a pad is placed under the shoe to protect the bottom of the foot,” says White.

Even though the horse may become sound, sometimes a fracture line can still be seen on radiographs. “These fractures tend to be very difficult to heal and see total resolution of the fracture line. Using scintigraphy, the increased bone activity can be detected for up to 22 months. Even though the horse is sound, the bone is still remodeling—even when it appears healed,” he says.

Surgical Repair with Screws – “When the fracture splits the coffin bone in half from the toe to the coffin joint, a bone screw can be placed across the fracture to give more stability to the fracture as it heals,” White says.

A hole drilled through the hoof wall is used to place the screw. Then the hole in the hoof wall is packed with wax or acrylic to keep it from becoming infected until the hoof wall regrows over the bone and screw head.

To accomplish this, the veterinary surgeon must have accurate measurements of the bone and hoof wall, and is guided by radiographic or CT imaging— after making a plan, designing exactly where the screw needs to go. “The surgeon makes a hole in the hoof, coring it out with a drill bit,” says Bertone. The screw goes into the bone through that hole, to stabilize and compress the fracture. It must be positioned in the exact center of the bone to pull the two pieces together.

“A recent paper stated that for mid-sagittal fractures (that go straight down the middle of the bone) a person should consider using two screws,” she says. This more fully stabilizes the fracture and prevents any movement, allowing it to heal quicker and more completely. This can significantly improve healing, giving the fracture the best chance to have a bony union rather than just a fibrous union.

In fractures at the extensor process, where a piece of bone is pulled loose at the top and front of the coffin bone where the tendon attaches, a screw can be used to stabilize the fracture if the piece is fairly large.

Removing Chip Fractures – “We also see some chip fractures in the coffin joint at the extensor process,” says White. These are not attached to the tendon, but just a small fragment which can be removed with arthroscopic surgery.

“Fractures on the midline (sagittal fractures) that might have a piece of bone or two up in the joint can benefit from arthroscopy—to scope that joint and remove any of those pieces,” says Bertone. “We can do that at the same time we are installing a screw. We anesthetize the horse, get a CT (computed tomography) image of the bone, a detailed image in 3 dimensions that tells us exactly what is wrong and what the fracture looks like, and then we scope the joint to remove any fragments. Then we can place one or two screws, depending on the size of the fracture,” she says.

Neurectomy – In some cases when the lameness is not completely resolved, a neurectomy—cutting the nerves at the heel—may be used. “This may decrease or eliminate the pain from arthritis and is a way to get some of these horses back into exercise when other treatments haven’t worked,” says White.

Bertone has treated many horses with wing fractures. “After being given 60 to 90 days in rim shoes, with anti-inflammatory treatment, we can nerve them and they go back to the race track sooner. The fracture may not be fully healed at that time, but they seem to continue to heal. It appears that racing while the foot continued to heal didn’t make any difference in the final healing,” she says.

“If a person wants to give the horse more time, such as a horse that isn’t in an athletic career, or any horse you might be able to give a year off from work, you could opt for conservative treatment and let it heal fully. We could give the horse 11 months off before doing any activity. But if you are in a rush to get the horse back out of the stall and back to work, giving it 60 to 90 days in the stall to let the healing start—and create a bit of a scar to stabilize it a little—followed by a neurectomy and carrying on can be very successful,” says Bertone.

PROGNOSIS

Non-articular wing fractures and rim fractures normally heal well, since they don’t affect the joint. There is no risk for arthritis and the horse can generally return to full soundness. “Depending on the horse’s use, about 50-60% of coffin bone fractures will heal with resolution of the lameness,” says White. “It depends somewhat on whether there’s a shift with disruption at the joint surface. In that case there is concern about developing arthritis later.” Supportive shoeing may be required when the horse returns to work, to prevent lameness.

Fractures affecting the joint, such as a crack down the center of the bone in front, take longer to heal and these horses are more lame. “When these heal, the two pieces tend to form a fibrous union rather than a bony union, and these take forever to heal,” says Bertone. “Several studies have shown that it takes a minimum of 11 months of rest, followed by a slow return to activity. It can be difficult to get these fractures to heal, to where the horse might have a chance to be athletic again,” she says.

“The limiting factor generally involves how much arthritis develops in the joint—which depends on how displaced the pieces are. Is it a 5 millimeter gap or a minimal gap, or no gap? It also depends on whether there is fragmentation of bone in the joint. A sliver or chunk of bone in the joint can be very detrimental. If a person doesn’t rest the horse long enough before trying to get back into work again, this type of fracture may not have a chance to heal. Those horses have more risk for arthritis, and then it becomes a long-term problem,” says Bertone.

You need time and luck. “There is some luck involved, based on how the fracture was created,” says White. “In any fracture that occurs acutely (with sudden lameness), the sooner it can be looked at, and a decision made regarding treatment, the better. This is especially true of certain fractures such as a fracture of the short pastern bone, because the longer the time before treatment, the more damage is done in the foot—which reduces the horse’s chances for good recovery,” White says.

With an acute foot lameness, don’t assume it’s just an abscess. “If it comes on very suddenly, it could be an abscess, but if there is any doubt, the horse should be examined by a veterinarian immediately,” White concludes.

SURGICAL RISKS

If the fracture must be stabilized, there are always some risks when going into the hoof for surgery. “Infection is the number one danger, since we are going in through the hoof wall, which is dirty,” says Bertone. “We always rasp and scrub it, and so far I have not yet had any of these get infected. But this is the biggest risk, especially if it’s not being done by someone who does these surgeries a lot,” she says.

“The second biggest risk is the fact that the hoof wall has to grow down over the head of the screw that you’ve placed, and the hole that you made, and sometimes it rubs against the inserted screw and becomes irritated. I’ve had horses be sore to hoof testers over that area. Even though there is no infection, there is scar tissue—essentially a knot in the foot. Probably in more than half of these cases, the screw needs to be removed at some point, after the fracture is fully healed, just because the screw might eventually cause a problem,” explains Bertone.

“This is something a person should plan for in advance. You need to put another hole in the hoof wall, at just the right location, to take out the screw. So again, it needs to be done by someone with experience,” she says.

COFFIN BONE FRACTURES IN FOALS

Foals heal swiftly, and generally have good prognosis. According to Paul Goodness, a foal may heal adequately with just a month of reduced activity. “Most of the foals simply have wing fractures or solar margin fractures. In these instances we generally don’t do anything special if they can be confined for 3 or 4 weeks—and are not running and playing out at pasture. If we can keep them quiet, with minimal activity, and leave the foot alone, these foals generally heal well. But if they have to be turned out, we must come up with some kind of tiny shoe to help immobilize that foot,” says Goodness.

Young animals heal much faster than adults, mainly because their bones are still growing. Everything happens fast, in a foal. The tiny shoe the farrier might put on the foal must be changed often, and a bigger one applied. “A rule of thumb when we do have to apply a cast or shoe: we remove it every two weeks and replace it. If you leave one on too long it will do long-term damage by restricting the hoof growth,” he says.

“We might bring the foal into a stall in the morning, take off the shoe or cast, and just leave him in the stall all day, and reapply the shoe/cast that evening and let him and mom go back to the field. I’ve had them heal up wonderfully well with this method,” Goodness says.