Equine Navicular Disease

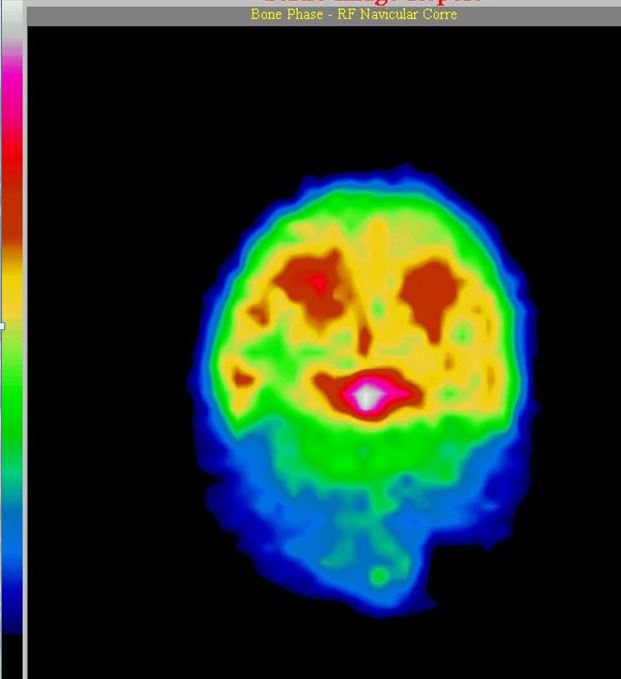

Nuclear scintigraphy, the best available imaging modality, showing white “hot spot,” The navicular bone is white hot, meaning there is a lot of bone damage. Photo courtesy Brian Burks DVM.

Equine Navicular Disease (Podotrochleosis)

By Brian S. Burks, DVM, Diplomate, ABVP, Board Certified Equine Specialist

Problems with the navicular bone are relatively common but are often treatable when found early. Navicular disease is a chronic, primarily forelimb lameness associated with pain from the distal sesamoid bone. Advanced navicular disease is associated with fibrillation of the deep digital flexor tendon, with or without adhesion of the tendon and the navicular bone. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has demonstrated abnormalities of structures around the navicular bone, including the collateral sesamoid ligaments, distal sesamoidean impar ligament, and the navicular bursa.

Historically, this has been considered a single disease, but given the variety of clinical presentations, it is likely that there a several clinical conditions with different etiologies that cause pain in the navicular apparatus.

Associated Risks

Conformation can lead to increased stress in the heels, predisposing the horse to degenerative changes of the navicular bone. This is common in quarter horses, which tend to have narrow, upright, boxy feet, small relative to body size. European Warmbloods often have tall, narrow feet. Thoroughbred horses have flat feet and low heels, with dorsopalmar foot imbalance.

Horses with small feet and narrow heels do not absorb and distribute concussion well and are predisposed to developing foot lameness. A broken foot/pastern axis (especially if the toe is long and the heels are short) places a tremendous amount of stress on the navicular region.

There is evidence of heritability of navicular disease in Dutch and Hanoverian Warmblood horses. Poor conformation may also be heritable in other breeds, predisposing them to navicular disease. The frequency of occurrence of navicular disease appears to vary between breeds. Quarter Horses, Warmbloods, and Thoroughbred cross horses have a relatively high incidence, whereas the Finn horse, Arabian, and Friesian have low occurrence of navicular disease. Finn horses and Friesian horses tend to have a straight or convex contour of the proximal articular border of the navicular bone and rarely develop navicular disease; horses in which the proximal articular margin is concave or undulating appear to be at highest risk of development of the disease.

Navicular Explained

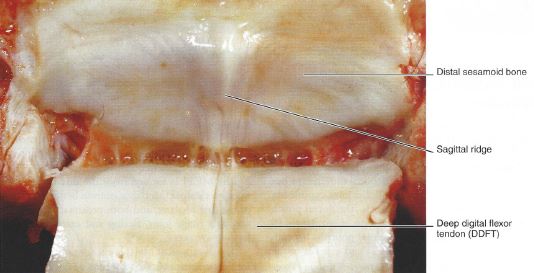

The navicular apparatus comprises the navicular bone, CSLs, DSIL, navicular bursa, DDFT and distal digital annular ligament. The navicular bone, which articulates with the middle and distal phalanges, provides a constant angle of insertion, and maintains the mechanical advantage of the DDFT, which exerts major compressive forces on the distal one third of the bone. The navicular bone is a small, cartilage covered, boat-shaped bone located at the back of the foot (the palmar/plantar aspect) behind the coffin bone (third phalanx) and under the short pastern bone (the second phalanx). The navicular bone, together with its synovial fluid filled bursa (a “sac” containing synovial/joint fluid), provides a fulcrum for the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) as it courses down the back of the foot. The tendon changes direction at the navicular bone before attaching to the bottom of the coffin bone.

The navicular apparatus comprises the navicular bone, CSLs, DSIL, navicular bursa, DDFT and distal digital annular ligament. The navicular bone, which articulates with the middle and distal phalanges, provides a constant angle of insertion, and maintains the mechanical advantage of the DDFT, which exerts major compressive forces on the distal one third of the bone. The navicular bone is a small, cartilage covered, boat-shaped bone located at the back of the foot (the palmar/plantar aspect) behind the coffin bone (third phalanx) and under the short pastern bone (the second phalanx). The navicular bone, together with its synovial fluid filled bursa (a “sac” containing synovial/joint fluid), provides a fulcrum for the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) as it courses down the back of the foot. The tendon changes direction at the navicular bone before attaching to the bottom of the coffin bone.

Signs

The clinical signs of navicular disease include bilateral forelimb lameness, although one foot is often more significantly affected. The onset of lameness is insidious. Lameness tends to worsen with hard exercise. The horse may exhibit pain during a hoof tester examination when placed across the central one-third of the frog to the opposite heel. An affected horse may ‘point’ one limb to relieve pressure on the caudal foot. Horses will land toe first or walk on their toes to relieve pressure in the heel area. Regional local anesthetic nerve blocks abolish the lameness. In a few cases, further information and localization of the lameness is done via intra-articular anesthesia of the coffin joint and/or the navicular bursa.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is dependent upon the lameness examination, including nerve blocks, and imaging modalities. The most common imaging is used is radiography; however, some horses with navicular disease do not have radiographic changes. Radiographs are relatively insensitive for bone change and the lack of change does not rule out navicular disease. Abnormalities that may be noted include an irregular shape to the bone, synovial invaginations (‘lollipops’) and loss of distinction between the cortex and medulla of the bone. Enlarged synovial invaginations are the result of recruitment and activation of osteoclasts following the course of the nutrient vessels into the spongiosa. There may be cyst-like structures in the central bone, an indication of adhesion between the navicular bone and the DDFT. There may be bone fibrillation at the flexor surface, another sign of DDFT adhesion to the bone.

Both MRI and nuclear scintigraphy are more sensitive to bone changes, and MRI is especially sensitive to soft tissue change, allowing a diagnosis to be made. Increased radiopharmaceutical uptake during nuclear scintigraphy indicates that there is increased remodeling of the bone and surrounding soft tissues, even in the absence of radiographic changes. MRI shows loss of fibrocartilage, which may extend to subchondral bone. It also shows fibrillation of the DDFT and changes to the DSIL and CSLs.

Treatments

The most important treatment for navicular disease/syndrome is corrective shoeing. Despite the severity of radiographic signs, shoeing recommendations will be similar. The foot needs to be at an appropriate angle, which may require a wedge pad. The toe should be shortened and rolled to decrease break-over, which is the point that the foot can come off the ground. The longer the foot stays on the ground and the horse’s body weight moves forward, the more pressure that will be applied to the heel region of the foot. To promote heel expansion, the shoe should extend behind the heels and be slightly wider than the heels. The nails should be set forward to encourage heel expansion. This type of shoeing should be performed every six weeks. Bar shoes are commonly used with pads or pour pads, but newer shoes include flip flops that provide excellent heel support but can flip off of the heel.

The most important treatment for navicular disease/syndrome is corrective shoeing. Despite the severity of radiographic signs, shoeing recommendations will be similar. The foot needs to be at an appropriate angle, which may require a wedge pad. The toe should be shortened and rolled to decrease break-over, which is the point that the foot can come off the ground. The longer the foot stays on the ground and the horse’s body weight moves forward, the more pressure that will be applied to the heel region of the foot. To promote heel expansion, the shoe should extend behind the heels and be slightly wider than the heels. The nails should be set forward to encourage heel expansion. This type of shoeing should be performed every six weeks. Bar shoes are commonly used with pads or pour pads, but newer shoes include flip flops that provide excellent heel support but can flip off of the heel.

The most common medications used to stimulate blood flow are isoxsuprine, pentoxifylline, and aspirin. It is not exactly known how isoxsuprine enhances blood flow, but several studies have shown that approximately 50% of horses with heel pain will improve with its administration. Isoxsuprine is a very safe, economical medication. Pentoxifylline changes the way red blood cells bend, making it easier to move through blood vessels. Aspirin is used for its anti-platelet affects; however, blood clots have not been found in horses with navicular disease. Phenylbutazone is the most common anti-inflammatory medication used. Keeping the horse comfortable, with a better stride and landing heel-first enhances blood flow. This medication has been associated with gastric ulcers, although older horses lived on phenylbutazone for many years, prior to our current knowledge. Another medication is firocoxib, or Equioxx. It is anti-inflammatory but does not have the GI side effects that other medications have.

If the response to oral medication and corrective shoeing is inadequate, the coffin joint and the navicular bursa can be injected with sodium hyaluronate and a corticosteroid. The latter increases the risk of infection in these areas and should be used judiciously.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ECSWT) or simply shock wave treatment has been found to be invaluable for many foot problems, but it must be used correctly, and must focus on the specific problem area. The foot must be soaked to allow these sound waves to penetrate the foot, and the machine should be a focused, not radial, shock wave machine. Different probes can be used, depending upon the depth of the problem. This modality benefits both soft tissue and bony abnormalities. Thus, fractures and navicular degeneration can be treated with ECSWT, as well as soft tissue abnormalities such as impar ligament and deep digital flexor tearing (desmopathy/tendinopathy respectively). This modality works by stimulating the production of healing cytokines in the area treated. It also stimulates the bone to regenerate, stimulating osteoblasts. By changing the settings on the machine, soft tissue versus bone can be affected. Impar ligament desmopathy almost invariably doomed a horse to the pasture in the past, but can now be effectively treated, and these horses are returning to their previous level of athletic activity, including jumping, dressage, and barrel racing. I have had many people tell me that their horse is much more comfortable and athletic following ECSWT. It has also avoided more invasive surgery in some (but not all) cases.

Another treatment to be considered is tiludronate (Tildren). This drug is similar to those taken by people with osteoporosis. It stops the bone from degenerating further by inhibiting osteoclasts, which break down bone, allowing the normal efforts of the bone to regenerate to catch up, resulting in bone healing. This is useful in fractures of the coffin bone, bony avulsion with ligamentous tearing, and navicular degeneration. I have helped a number of horses return to normal activity with the use of tiludronate. OsPhos is a similar medication given in the muscle.

Surgery

When conservative therapy has proven ineffective, surgery may be necessary. Surgical therapy includes transection of the inferior check ligament (ICLD) and palmar digital neurectomy. The inferior check ligament begins at the back of the carpus (knee) and inserts on the deep digital flexor tendon. When the DDFT has become adhered to the navicular bone and can no longer stretch, taking a section of this ligament will allow adequate stretching and a reduction of the mechanical lameness. It will take the pressure off the navicular bone and the impar ligament. Neurectomy- cutting and removing a portion of the nerve below the fetlock- is usually reserved for horses with severe lameness localized to the back of the foot. By removing a section of the nerve, and “capping” the axons with the nerve covering, many, if not all, of the complications of the surgery can be avoided. A neurectomy does not change the disease process, whereas the desmotomy seeks to prolong the useful life of the navicular bone.

If possible, these horses are maintained in work. Turn out encourages moving but may not be enough; riding or lunging may be necessary. The prognosis for horses afflicted with navicular disease is generally favorable; many of these horses will return to full athletic use. Corrective shoeing will be required for the horse’s entire career.

Navicular disease is often thought of as a death sentence, or at least that the horse can no longer be used. Many horses with navicular disease, when treated appropriately, can still perform at their previous level of activity.

Fox Run Equine Center

(724) 727-3481

Providing quality medical and surgical care for horses since 1985.