Ebola, You and Your Horse

Click here to read the complete article

By Megan Arszman

The news headlines sounded like they were straight out of a script from a major motion picture. A disease, once thought to no longer be a threat, sweeps across villages in West Africa causing numerous deaths and overwhelms local clinics. The disease then infects the very care workers sent in to help. Unknowingly, some of those infected travel back home, potentially spreading the disease from a Third World country to one of the most powerful and richest nations in the world.

Ebola is a word, that when uttered, can cause even those with nerves of steel to anxiously look for the nearest hazardous material suit. From March, 2014 to November, more than 16,000 human cases of Ebola virus were reported in West Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

History of Ebola

Ebola was first discovered in 1976, in what is now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo near the Ebola River. Before the 2014 outbreak, there had been only 32 Ebola outbreaks between 1976 and 2014, a total number of cases of 2,361—1,438 of those ending in death, according to the World Health Organization.

Ebola hemorrhagic fever can be caused by one of five different Ebola viruses. However, only one strain has been found to cause illness in some animals, but not humans. The other four strains can cause severe illness in both humans and animals.

One misconception is that Ebola is extremely contagious. While it is very infectious, because it only takes a tiny amount of the virus to cause illness, the virus is not transmitted through the air (unlike influenza or the measles). Contact with bodily fluids from an infected person or contaminated objects from infected persons can cause infection. Experts believe natural hosts for the virus are fruit bats.

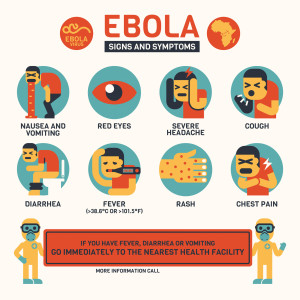

Symptoms of Ebola can mimic the flu: fever, aches, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, and stomach pain. Those suffering from the virus have also claimed to experience a rash, red eyes, chest pain, difficulty breathing or swallowing, sore throats, and some bleeding (internally and externally).

Cases in the U.S.

The 2014 outbreak began in March following the news of 23 deaths that were the result of a “mystery” hemorrhagic fever in Liberia. The first American cases were reported to be Dr. Kent Brantly and missionary Nancy Writebol, who were working for aid groups in Monrovia, Liberia in July. Both individuals were flown to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Ga., in August for treatment. The first causalty to take place in America as a result of the outbreak was Thomas Eric Duncan, who came to the United States from Liberia to visit family in September. He later died in October at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. As of press time, there had been four reported cases in the United States.

Prevention and Treatment

The best way to prevent infection of the Ebola virus is to avoid the hot zones of the epidemic. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), there are four levels that indicate a person’s risk of infection.

High Risk—Coming into direct contact with someone who has contracted Ebola, when not wearing personal protective equipment, via a needle stick, getting bodily fluids directly on the skin or splashes to the eyes, nose, or mouth. Also, any persons living with and/or taking care of someone with Ebola are at high risk.

Some Risk—Coming in close contact (being within three feet for a long period of time) with someone sick with Ebola in a house, healthcare facility, or within the community while not wearing personal protective equipment. You might also be of some risk if you came into direct contact with a person sick with Ebola in a concentrated zone while wearing your personal protective equipment correctly.

Low (but not Zero) Risk—If you’ve been in a country with a large Ebola outbreak, within 21 days, but with no known exposure (meaning no direct contact with body fluids from victims), or if you traveled on an airplane with someone sick with Ebola, had brief direct contact (shaking hands) with someone sick with Ebola, or being in the same room for a brief period of time with an Ebola patient.

No Risk—Contact with a healthy person who’s had contact with a person sick with Ebola or with someone sick with Ebola before any symptoms were shown means you have no risk. Also, if you’ve been in a country where there might have been Ebola cases, but not a large outbreak, there is no risk.

As of right now, there is no vaccine to combat Ebola that has been approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA). To treat the virus, doctors and nurses simply treat symptoms and complications as they appear. Some means of treatment include using intravenous fluids and balancing electrolytes to keep the patient hydrated; keeping a level oxygen status and stable blood pressure; and treating other infections as they occur.

There have been patients who have survived from infection because of their immune response and the supportive care they received. Survivors develop antibodies that can last at least 10 years, but it is not known if that deems them immune for life if they were to come in contact with the same species of Ebola or a different type. Some survivors have developed long-term complications such as joint or vision problems.

Animals and Ebola

If you are in Africa, you can spread Ebola by handling wild animals that are hunted for food. There have only been a few mammals that can become infected with, and spread, the Ebola virus, such as humans, monkeys, and apes. There hasn’t been any evidence that insects such as mosquitoes can transmit the virus.

Some of the more popular headlines that have come out of the 2014 outbreak referenced stories of dogs, belonging to Ebola patients, being quarantined or even humanely euthanized because of the fear of spreading the disease. The CDC has reported little evidence that dogs can become infected with the Ebola virus and no evidence that they can develop the disease.

In the United States, there have been no reports of dogs or cats becoming sick with Ebola or transmitting it to their humans.

What about horses? Limited testing has been performed on different species of animals when it comes to the infection and spread of Ebola, including the horse. Horses have been infected experimentally and did not show any symptoms of the disease. Beyond that, there has been very little research as to why horses, or other species, might be immune to the disease.

Biosecurity for Horses

If you’re still concerned about Ebola and biosecurity on the farm, practicing a few simple steps to keep germs from spreading is the most important.

One of the first things to do is to set up a quarantine area where you can isolate sick horses from healthy horses. Make sure sick animals (horses or otherwise) cannot come into contact with healthy animals. For horses, that includes nose-to-nose contact, whether it’s through the fence or stall walls.

However, experts agree that proper biosecurity practices should be implemented every day, not just when you see a sick horse on the farm. Dr. Nicola Pasterla comments, “Biosecurity needs to applied every day and not only during an outbreak situation.”

This means working with your veterinarian to come up with an infection control plan, especially for training barns that might have horses coming in and out on a regular basis. Your veterinarian can evaluate your farm and activity level to help come up with the right plan of action, which will include vaccinations and other prevention protocol.