A Valentine’s Miracle: The Horse With A Squeezed Heart

Penn Vet Extra- Squeezed Heart

By: Louisa Shepard

The bright Thoroughbred filly with the intriguing name Five Smooth Stones is ready to start her gate work at Fair Hill. With a broad muscular chest, standing just over 15 hands at two years old, this beauty with a wide blaze is perfectly suited for a career on the racetrack.

Such a surprise, then, to learn that six months earlier she came to New Bolton Center on emergency with a life-threatening heart condition. After days of fighting a bacterial infection and high fever, her heartbeat was impossible to detect, the sound so muffled by fluid.

“I kept listening and listening and I could not hear her heart,” said Dr. Carolyn Littel, her primary veterinarian, about the exam in August. She had been monitoring the filly that week, treating her with antibiotics. “She was at her worst.”

Littel thought back to a rare condition she learned about as a veterinary student. “I thought of pericarditis, but I had never seen one in my career,” said Littel, who graduated from Penn Vet in 1994.

An ultrasound examination performed by Dr. Mary Durando at the farm confirmed the diagnosis of the dangerous cardiac condition, and they recommended the filly go to New Bolton Center immediately.

Owner Norris Gelman, a Philadelphia attorney, did not hesitate to approve treatment. “We bring them into the world and hope they do well and make some money for us,” he said. “If they need help along the way, we can’t say that’s too much. I owe her that.”

Five Smooth Stones

The filly’s name is a reference to the Biblical story of David and Goliath. David chose five smooth stones from a stream, which he used to fight the giant, using a slingshot. “I was hoping she would be a giant killer,” said Gelman.

But everyone calls her Squirrel, a handle coined by trainer March Walsh, who raised the orphan foal. Squirrel’s dam, Chords of Fame, Gelman’s best brood mare, died when the filly was two months old. Her sire is the successful Rimrod.

“I have high hopes for Squirrel,” Gelman said.

New Bolton Center Emergency

The Emergency and Critical Care team knew the possible diagnosis and checked Squirrel’s heart immediately upon arrival at New Bolton Center. Her heart rate was 95 beats per minute; a normal heart rate is in the 30s.

VIDEO- Ultrasound of Squirrel’s heart before catheterization

“Anything above 60 is concerning,” said Dr. Neil Mittelman, the Internal Medicine Resident in Emergency assigned to her case. “The horse was in dire straits.”

Dr. Virginia Reef, world-renowned for her work in equine cardiology, conducted the echocardiogram, which revealed a “significant” amount of fluid in the pericardial sac that surrounds the heart.

“We were all set up and ready when she walked through the door. It was very clear the fluid needed to be drained,” Reef said. “There was so much pressure on her heart.”

The pressure created by the fluid makes it impossible for the heart to fill with blood, causing it to beat harder and faster, she said. The horse can collapse and die.

The solution is to insert a chest tube into the pericardial sac to drain the fluid.

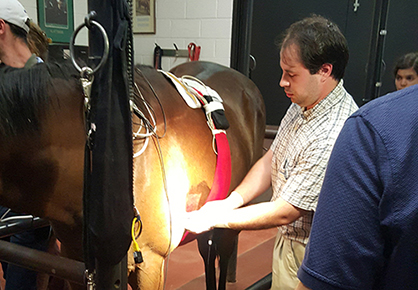

Dr. Neil Mittelman places a cathether into Squirrel’s pericardial sac to drain the fluid.“Under ultrasound guidance, Dr. Reef instructed me on exactly where to place the drain,” Mittelman said. “We put a large tube through her skin and between her ribs, tunneling into the sac that surrounds her heart.”

The fluid came gushing out, as if from an open faucet, more than eight liters in the first 15 minutes. Within an hour, Squirrel’s heart rate was down to about 80 beats per minute, Reef said. Also, the left ventricle of her heart expanded from 6 centimeters to 8.5 cm.

The next stage of treatment, pioneered by Reef in the 1980s, is critical to long-term function of the heart: repeatedly flushing the pericardial sac with saline and infusing the area with antibiotics.

Without this treatment, the sac can form scar tissue that will create permanent adhesions onto the heart and restrict the function for life.

Dr. Gretchen Verheggen flushing Squirrel’s pericardial sac.“The heart is in a sac, kind of like an old-style washing machine: the heart is the rotor, and the sac is the drum. We can flush that sac to get out the fibrin and inflammatory mediators, and put in antibiotics,” said Reef, describing the treatment she created, now used widely throughout equine medicine.

VIDEO- Ultrasound of Squirrel’s heart after drainage

Responding to Treatment

Mittelman said they lavaged Squirrel’s pericardial sac twice a day with fluids containing antibiotics. “We were continually monitoring her heart rate and rhythms,” he said. She was also receiving IV antibiotics, as well as steroids, in case the cause was an autoimmune reaction.

The tube was in the sac for three days, until the fluid completely stopped draining, Mittelman said. An ultrasound examination confirmed there was no residual fluid.

“She was already starting to look brighter,” he said. “She was much more comfortable and her heart rate was dropping.”

By the time Squirrel was discharged after 12 days in the hospital, her heart rate was normal and the left ventricle of her heart was a normal 10 cm, Reef said. Also, her kidneys, which had been stressed due to lack of blood flow, returned to normal.

Squirrel went home on oral antibiotics, and stall rest. “She continued to make steady progress and never looked back,” Mittelman said.

The cause? Unknown. Fluid samples showed some cells that might indicate a bacterial cause, but no bacteria grew on culture. Test for viral causes were also negative.

Reef said bacteria, viruses, and an immune-mediated response can all trigger the condition. “Most of the time we don’t know what the cause is,” she said.

A Breakthrough Treatment

Before Reef’s pioneering treatment, the prognosis for pericarditis was “really grim,” she said, because the surfaces would stick together after simply draining the area. The prognosis using her treatment is “really favorable,” today, she said.

Reef published about her first case in 1984: “Successful Treatment of Pericarditis of a Horse.” She then published on six more cases in 1990.

Reef is Director of Large Animal Cardiology and Diagnostic Ultrasonography and Chief of the Section of Sports Medicine and Imaging at New Bolton Center.

“The horses that I’ve treated have done really, really well,” she said, including Squirrel. “I don’t think she’ll have a problem again.”

At the last re-check at New Bolton Center in November, Squirrel was cleared to return to race training. This was as optimal an outcome as anybody could have expected,” Mittelman said, “a best-case scenario.”

Back In Training

It’s a blustery February day at the Oxford barn of trainer Bobby Manchio, of Manchio Racing. Squirrel is clearly enjoying a visit from Walsh and Littel.

“She’s my girl,” said Walsh, as the filly popped her head out of the stall, looking for treats.

Manchio said Squirrel, a sweet and willing horse that learns quickly, is coming along extraordinarily well in her training.

Squirrel enjoying peppermints from trainer Bobby Manchio and Dr. Carolyn Littel.“Everything is normal. If I didn’t know what went on, I couldn’t tell,” he said. “You don’t have to cut her any slack. She has had an absolutely normal progression, if not a little better. She is tough.”

Manchio speculated that she will run her first race in about three months, and will get going on her starting gate work at Fair Hill Training Center this week. “She’s ready to start breezing,” he said.

Owner Gelman is looking forward to watching her progress.

“We put her in position to have a very good racing life. We hope she does, but if she doesn’t, I want her to have a good life,” said Gelman, who has had many horses over the years, and currently has five. “They are magnificent animals and we have a high obligation to them.”