Equine PET Imaging Isn’t Just For Racehorses Anymore!

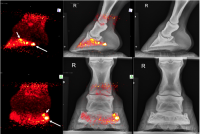

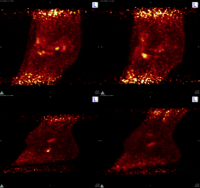

PET imaging of a horse’s right hock with the MILEPET scanner at the UC Davis veterinary hospital.

UC Davis

By: Rob Warren

Standing equine positron emission tomography (PET) imaging is not just for racehorses anymore. In the first four months since the installation of the MILEPET scanner at the UC Davis veterinary hospital, 100 horses have been imaged; more than half were performance and pleasure horses.

Fractures in horses are often fatal, so diagnosing and preventing these leg injuries are essential to equine health. Pioneered at UC Davis in 2016, equine PET imaging initially required horses to undergo general anesthesia, with 150 horses imaged over five years. Modifications to allow PET imaging on standing horses under sedation greatly increased its applications.

Under the guidance of UC Davis veterinary radiologists, the original MILEPET scanner has been in use at Santa Anita Park since December 2019, where it has provided imaging at the molecular level to monitor racehorse health and guide training and medical care. In a year and a half, more than 200 racehorses have been imaged with the scanner, several on multiple occasions. In addition, the increased safety, reduced costs, and improved ease of use of the new scanner is now also responsible for the expansion of its use into other disciplines.

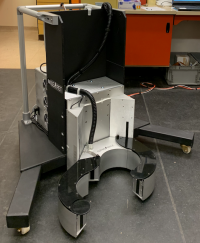

The MILEPET scanner, with the detectors in an open position.

PET imaging has become simple with the MILEPET scanner. A small dose of a radioactive dye is injected about 30 minutes prior to imaging. This dye distributes through the body and accumulates at sites of active injuries. The horse is then sedated similarly as with many veterinary procedures, such as taking X-rays. The scanner is wheeled up to the horse and an openable ring of detectors loosely closes around the limb. It takes between 3-5 minutes to image each site. In less than 30 minutes, both front feet and both front fetlocks can be imaged.

Of the recent 100 horses imaged at UC Davis, 45 were racehorses from Golden Gate Fields. The main area of focus in these horses is the fetlock, as this is the most common site of injuries that can lead to catastrophic breakdowns. The other 55 horses represent a diverse population of UC Davis veterinary hospital patients, including high-level showjumpers, western performance horses, and pleasure horses. In this population, hooves and fetlocks have been the areas most commonly imaged, as they are the most common sources of lameness.

Standing PET has also been successfully utilized for imaging of the hock. Lameness localized to the hock can be challenging, as X-rays and ultrasound are inconclusive in a number of cases. Standing hock MRI is difficult because the horse needs to remain still for 45 minutes. Within 10 minutes, a PET scan can help identify arthritis or suspensory issues as the cause of the lameness.

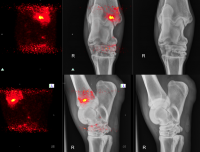

Radiographs alone of foot lameness show unremarkable results. But when fused with PET, a collateral ligament attachment injury and a bruised heel are revealed.

“Beyond the impressive numbers, the type of cases scanned has also changed,” explained Dr. Mathieu Spriet, the radiologist leading equine PET development at UC Davis. “PET used to be considered the last imaging resort when all other imaging modalities had been exhausted and more information was still needed. Now, PET can be considered as an option earlier in the diagnostic process.”

Different imaging modalities can also be combined to provide the most accurate picture. In some cases, PET and X-rays will provide all the information necessary to decide on a treatment plan. In other cases, MRI of a specific area can be performed after PET, and the combination of PET and MRI data provides the most comprehensive assessment of the situation.

Horse with a hock infection. The PET identifies an area where the infection extends into the bone.

Another interesting novel application of PET is for the assessment of laminitis. This severely debilitating condition can be difficult to manage, and monitoring the activity of the disease is particularly important for adapting trimming and shoeing to make the horse comfortable. PET provides information not only on the inflammation present in the hoof, but also about the health of the coronary band, the area responsible for hoof growth.

PET images of both front feet and both front fetlocks of a Quarter Horse. A navicular injury in the left front foot (arrow) is the main reason for the lameness, but there is also evidence of mild arthritis in both fetlocks.

“It is exciting to see an imaging modality that started here as a long-shot idea more than six years ago to now be in full clinical use at the UC Davis veterinary hospital,” said Dr. Spriet. “The continued support from our Center for Equine Health and the collaborative work with LONGMILE Veterinary Imaging have been paramount to this success.”

The use of PET will keep growing in the sport and pleasure horse populations. Ease of use and affordability make it an excellent first choice for advanced imaging, as the costs and time to image two feet and two fetlocks with PET are less than for the MRI of a single foot. In addition to being used for identification of an injury, the “functional” imaging properties of PET—assessing the activity of injuries—are particularly helpful for monitoring rehabilitation.