When Does Training Cross the Line?

Click here to read the full article in our digital edition.

by Susan Winslow

In the late 1970s, I took some time off from college to work in a well-respected barn while contemplating a major in Equine Science. It meant 65 hour work weeks for a mere $100 paycheck, but I was so excited just to be in the small orbit of an internationally famous trainer with rock star status. I probably would have worked for free. I learned a lot during that experience, but it wasn’t the lesson my ridiculously naive 18 year-old self hoped for when I took the job.

In the late 1970s, I took some time off from college to work in a well-respected barn while contemplating a major in Equine Science. It meant 65 hour work weeks for a mere $100 paycheck, but I was so excited just to be in the small orbit of an internationally famous trainer with rock star status. I probably would have worked for free. I learned a lot during that experience, but it wasn’t the lesson my ridiculously naive 18 year-old self hoped for when I took the job.

As an employee on the lowest rung of the barn hierarchy, I was a chief stall mucker. In a matter of weeks, I developed a soft spot for one special horse. Even though he was a high priced youngster with the potential to be a superstar, the horse’s irresistible charm was his sweet nature and impish curiosity. Cleaning his stall became a comedy routine as he searched for treats in a pocket or tried to ‘help’ with the pitchfork. It was impossible not to fall in love with him.

Looking back to a blazing hot August day, I now realize the combination of big-name pressure to produce results, an owner paying big bucks, and the horrid summer heat may have created the perfect storm for that poor horse. In an afternoon training session, he received such a savage beating from my idol that he tied up and the vet had to be called in. Barn staff was told to keep quiet, and I am ashamed to this day that I was too intimidated to speak out. I never forgot the sight of that horse with his head down, covered from his poll to his dock in hot, ugly welts, truly broken in body and spirit. I took some time away from horses, and that event alone inspired me to follow a different career path.

Fortunately, the majority of people who dedicate their lives to horses are decent, hard working professionals who do it for the love of the animal and the desire to produce quality horses and riders they can be proud of. Also, there has been an evolution in training, with more humane methods gaining acceptance over abusive tactics that create learned helplessness or a broken spirit. Additionally, camera phones, video monitoring, and internet surveillance play a role in accountability.

There isn’t a horseman alive who hasn’t had a moment of frustration at some point, whether it’s from fear, ignorance, or misunderstanding, but when does training cross the line into abuse? The Equine Chronicle spoke with some leading trainers in the industry who have gained respect for both their championship horses and their humane approach to creating those champions. Their thoughts on a fluid and often-controversial topic can serve as a springboard for further discussion on the state of the horse industry today and tomorrow.

Troy Compton, owner of Troy Compton Quarter Horses in Purcell, Oklahoma, has produced thousands of world-class show horses. He offers the following thoughts:

Troy Compton, owner of Troy Compton Quarter Horses in Purcell, Oklahoma, has produced thousands of world-class show horses. He offers the following thoughts:

“Abuse occurs when a person loses control of a situation. It comes from a lack of knowledge, self-discipline, and self-control. I’ve seen it happen with the two domestic animals that have the intelligence for us to train them: dogs and horses. Like any athlete, sometimes you have to stretch until it hurts to get the benefits and push to the next level, but there’s a big difference in doing that and going over the line into abuse.

“I see it in western pleasure horses, where it’s often a matter of style. Some horses are pushed to an extreme, and you can see it in their movement. In western pleasure, we ride on a loose rein, and the key is to make it look natural and easy. When you see a horse out there that’s moving like a machine, going through the motion without any light or emotion, that’s when it has crossed the line. People sometimes forget that these are thinking, feeling beings with emotion. You can tell when a horse enjoys his job and is moving with willing, natural movement. I want my horses to move correctly, but I want them to enjoy the job they’re asked to do, and abuse creates the opposite. People sometimes forget that this is supposed to be fun for both the riders and the horses.

“When I see a horse that’s rubbed raw on its sides from spurs, I see abuse there, too. If you’ve got your leg on the horse, and the horse doesn’t understand; move your leg. Don’t just spur the horse in the same spot until it’s raw. Those scars are visible on the outside, but that kind of abuse creates emotional and psychological scars on the inside, too. Unfortunately, there is no license to become a trainer, so anyone can say he or she is a trainer. Many horses suffer because of novice mistakes. I get a lot of those horses in for retraining, and I take them back to square one and give them a chance to succeed. I’ve also been in this business a long time, and I’ll be honest with a client if I think a horse isn’t right for them, rather than force a horse into a job it isn’t suited for.

“I think we’ve made great strides in the past two years. Allowing the public to come through the barns at shows and see the horses has helped curb some practices. Educating people on riding the horse through the ears is also a step in the right direction. By that, I mean watching the horse’s ears to read what it’s telling you. I want my horses to end each ride on a positive note, even if it has been an intense training session. I’ll take that horse for a fun lope around to make sure it ends our ride in a good place mentally. This is important, because I want the horses I train to be as safe for an 85 year-old grandmother as they are for a 5 year-old child. That comes only through time, patience, and a training regimen that allows the horse to learn through success, not abuse.”

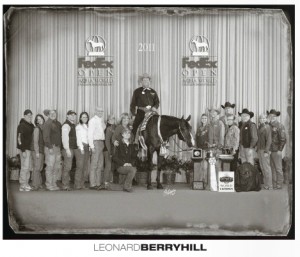

Leonard Berryhill, owner of Berryhill Quarter Horses in Talala, Oklahoma, is a multiple World Champion trainer with over thirty years in the equine industry. He says, “Training crosses the line to abuse when the person stops thinking about the animal as a thinking, feeling being and forces that animal into a role that isn’t right for that horse. I see it when people never let their horse relax. They never leave their hands and feet alone, and that horse never has a positive, relaxing moment in the ride. A horse should be soft in the bridle and go with a willing, relaxed movement. A horse that’s going with a mechanical movement and a dull, dead eye is a horse that has been pushed too hard and has given up. I don’t ever want to see that in a horse. Will a horse that’s been abused be able to recover? It’s about 50/50, and it can take a long time for the horse to come back from abusive treatment.”

Leonard Berryhill, owner of Berryhill Quarter Horses in Talala, Oklahoma, is a multiple World Champion trainer with over thirty years in the equine industry. He says, “Training crosses the line to abuse when the person stops thinking about the animal as a thinking, feeling being and forces that animal into a role that isn’t right for that horse. I see it when people never let their horse relax. They never leave their hands and feet alone, and that horse never has a positive, relaxing moment in the ride. A horse should be soft in the bridle and go with a willing, relaxed movement. A horse that’s going with a mechanical movement and a dull, dead eye is a horse that has been pushed too hard and has given up. I don’t ever want to see that in a horse. Will a horse that’s been abused be able to recover? It’s about 50/50, and it can take a long time for the horse to come back from abusive treatment.”

While Berryhill is honest about the fact that some of the extreme measures used on horses in the past, under the guise of training, may still exist with some trainers, he believes there have been vast improvements in recent years. He says, “Education is the key to instilling better training methods, especially in upcoming generations. When I was coming up, I didn’t have a trainer to work with. I just sat along the rail and learned from watching the trainers I emulated. As trainers today, we have the responsibility of setting an example as good horsemen, not just trainers. If you watch, you’ll also see that the clients ride just like the trainer does. We have a responsibility to promote good training methods and respect for the horse. There will be those horses that aren’t right for the job, and it’s also our responsibility to be honest with our owners, if that’s the case. These days, competition is so expensive and specialized. The horse has to be well-suited for the job we’re asking it to do if it’s going to do well in the show pen.”

Berryhill gives credit to the organizations that have taken steps to change industry standards toward more natural movement, particularly in the western pleasure horse. He says, “The NSBA, AQHA, and others have done a good job of addressing this issue and making changes in their organizations. The horse is allowed a more natural head carriage, and that’s a good thing. Today, there is also much more trainer visibility and policing at shows than there was years ago. We also police ourselves, and people will speak up if they see something like a horse covered with spur marks on its sides. I am seeing much happier horses out there as a result of these changes.”

Jay Jordan, owner of Jay Jordan Show Horses in Comfort, Texas, is a well-respected horseman, breeder, trainer, judge, and World Champion in his own right. With many years in the industry, he has seen plenty of the good and not so good. He echoes the sentiments of Compton and Berryhill when he says, “Abuse occurs when you try too hard to put a square peg in a round hole. By that, I mean you’ve pushed a horse into a job it isn’t well suited for, isn’t happy with, and it just doesn’t fit.”

Jay Jordan, owner of Jay Jordan Show Horses in Comfort, Texas, is a well-respected horseman, breeder, trainer, judge, and World Champion in his own right. With many years in the industry, he has seen plenty of the good and not so good. He echoes the sentiments of Compton and Berryhill when he says, “Abuse occurs when you try too hard to put a square peg in a round hole. By that, I mean you’ve pushed a horse into a job it isn’t well suited for, isn’t happy with, and it just doesn’t fit.”

He believes that a good trainer knows how to observe and calculate the variables in both the horse and the rider to make sure that situation doesn’t happen in the first place. “You have to remember that trainers and exhibitors, who have been in this industry for the long haul, really must have a true passion for the horse or we wouldn’t last this long. You have to start with the right ingredients to determine which horse has the potential to be a good novice, open, or non-pro horse, and that comes with knowledge. Then, you have to be able to work with the client to help them determine appropriate goals and find the right horse to fit those goals. When you make that correct match and set appropriate goals, then you work to help that team to gain confidence in each other to do the job in competition.” The key, he says, is to do it in a way that’s a good experience for both of them.

When that basic formula is ignored, Jordan believes it can lead to abuse, if the trainer isn’t careful. “When a person consciously pushes a horse beyond what he knows is right for that horse, you start to slip over the line into abuse. Heck, we’ve all had moments when we’ve made an honest mistake or wish we could do something different with a horse. Perhaps, after the fact, we’ve gained more knowledge, but that’s different than knowingly putting the horse in a position where there is no escape or reward to the point where the horse loses all confidence in itself. When you lose sight of what you’re doing, where you’re going with that horse, and what your goals are, it’s time to re-evaluate what you’re doing before you come up against that line. You have to also consider the rider and make an honest evaluation of goals. You can’t put a novice racecar driver in the Daytona 500 the first time out. The same thing goes for exhibitors in show pen. If you push too fast, too soon, that can harm both the horse and rider. It’s the trainer’s job to ensure that the horse and rider are a good fit, the horse is properly prepared for the job, and the horse and rider team are ready, both physically and mentally, to go out there and do their best. They can’t do that if they’re stressed to the point where the rider is melting down before a class and the horse is miserable.

“It all goes back to insecurity. As horse trainers, we are teachers for both the horse and rider. It’s just like a kid; if you’re trying to teach a kid something and all that kid gets is knocked down every time he tries to understand what you want him to do, you’ll lose the trust. In place, there will be bitterness and shutting down. With horses, it’s the same thing, and it’s important for us as trainers to admit when we may need a mentor or help from someone else who might see something we don’t.”

Jordan has seen improvements in the industry, and he’s optimistic about the future. “Take the western pleasure classes. For so many years, those horses were forced to go like they all came out of a cookie cutter. Organizations like the APHA, NSBA, AQHA, and others have done a good job of trying to improve the standards so horses aren’t all forced to go like that. We’ve done a good job of moving away from such a tight standard that was almost impossible for most horses to fit. Consider this: I’ll never be a ballerina. If someone told you that you had to make me into a top ballerina, you’d get frustrated pretty fast trying to make me become one. I’d be so stressed and defeated that eventually I’d shut down. The industry now understands that we can’t do that to horses, and, as judges, we’re responsible for applying the standards that allow the horse to be successful in its job by not forcing them into cookie cutter movement. When the horse is in a job it can do, that horse is able to have many more years ahead of it, and that’s good for the horse and the rider.”

He believes it’s easy to spot a horse that has been abused. “Whether it’s in the pasture or the show pen, you can tell that horse by its general appearance and demeanor. If you see a horse that’s got its ears pinned and an empty eye, you can tell it isn’t happy.” Jordan has been able to rehabilitate horses that have been down that tough road, and he says, “Horses aren’t naturally violent animals, and they don’t naturally want to hurt you, but they will fight if they are boxed in. You have to take a horse that’s been abused back to a complete reprogramming process to gain that horse’s trust again. It can be done, but it can take a long time, depending on that horse.”

Based on his experience, he has a positive outlook for the future of the industry. However, he has seen that with greater visibility through social media, there is a heavier responsibility to educate the public. He says, “As professionals, it’s our job to educate people. There was an incident at a show where someone put out a video of the warm-up ring. It totally misrepresented what was happening as abuse because the person didn’t understand horses or take the time to ask questions. They just made a snap judgment, and then it was out on the internet. Social media is a great thing, but it can also be a dangerous thing when someone puts something completely out of context. It’s our job as trainers and exhibitors to reach out to people at shows who may not understand what we’re doing, so we can let them know how much we care for these animals and the sport. People are realizing that it’s more beneficial to the entire industry to welcome people in and promote the family aspect and longevity of the sport over one-shot slot classes and quick money. This benefits the horses, too. At the end of the day, what we want is to help people discover a sport that the entire family can enjoy for a long time. That benefits all of us.”