Unique Pool Recovery System Helps Horses Wake Up From Anesthesia

(Reprint permission provided by New Bolton Center)

By Corinne Sweeney, Associate Dean for New Bolton Center

The reputation New Bolton Center has built over the decades for providing the best care for equine athletes is due in part to our unique “pool recovery” system, designed for horses to awake safely from anesthesia. Dedicated 40 years ago, the pool system, created at New Bolton Center, was the first-of-its-kind, a critical innovation in veterinary surgery. Today, the updated recovery pool continues to be an integral tool used by our equine orthopedic surgeons for patients with leg fractures.

“The pool can make all the difference in a successful recovery, especially in the most extreme cases,” said Dr. Dean Richardson, Chief of Surgery at New Bolton Center. “Waking up from anesthesia in the pool gives horses a chance to safely recover their strength, coordination, and awareness, and that provides a much better chance for them to recover without injury.”

Dr. Jenny Takes on the Challenge

From the earliest days of equine surgery under anesthesia, veterinarians recognized that there were enormous risks during the recovery phase. Horses are prey animals, and their instinct is always to run away from trouble. Every time a horse awakes from general anesthesia, it will attempt to stand and run before it fully recovers its coordination and strength. In most instances, horses still manage to rise and recover. But a horse recovering from a repaired fracture will often overload the repaired limb so severely that the entire surgical repair can catastrophically fail, even in a padded stall. The consequence is a “successful” surgery, but a euthanized horse.

In the late 1960s, Penn Vet’s Dr. Jacques Jenny – often referred to as the “father of equine orthopedic surgery” – optimistically determined that there must be a solution to this challenge. His idea: a carefully designed pool-raft system that would allow the horse to safely regain consciousness following anesthesia. Use of a raft within a pool system would allow the horse to float, decreasing or eliminating the re-fracturing of the just-repaired limb.

Wanting to test out his pool recovery theory, Dr. Jenny had a hole dug in the paddock adjacent to D barn at New Bolton Center, lined it with plastic, and filled it with water. He hired the crane operator who was working across the road at the Upland Country Day School to come over and help test out his hypothesis. The crane lifted the anesthetized horse, which was in a sling, and placed it into the newly created pool. Once the horse recovered from anesthesia, the crane then lifted the horse out of the pool.

Dr. Loren Evans, Professor Emeritus of Surgery, described the event in a 2007 letter, painting an almost-comical scene. “That sling was a far cry from the slings developed later on,” he wrote. “As the crane operator was lifting him out, the horse nearly slipped out of the sling, creating quite the scene.”

Mary Hazzard was a certified nurse in the New Bolton Center Section of Anesthesia at the time. “It was a cold, cold day. So cold that it was difficult to get the halothane to vaporize to anesthetize the horse,” Hazzard said in a recent interview. “While is was a brilliant idea and the beginning of what we have today, it was lucky no one was killed. To test this theory was really taking a chance.”

The first of two horses tested was an Appaloosa, Hazzard said. The water was very cold, she said, and the raft was too small. There was no head piece on the raft, so the horse’s head hung over the side and almost into the water, so the nurses had to hold it up. There wasn’t a clear plan on what to do with the horse once they got him out of the sling. Not surprisingly, given the imperfection of the plan, as the horse lied on the ground, he developed a muscle disorder commonly called “tying up,” from which he recovered.

Despite these early challenges, the creators persevered. “We kicked on,” Hazzard said. “Dr. Jenny had a vision and it came to fruition.”

Many lessons were learned. Clearly the raft needed modifications to prevent the head from hanging in the water, and to allow easier placement and removal of the horse. Ray Firestone from the Firestone Rubber Company, a client and friend of New Bolton Center, lent two of his engineers to help in the development of the recovery pool raft that is currently used, Dr. Evans said.

It also was recognized that the cold water likely contributed to the development of tying up. “We learned water temperature had an important role in the welfare of the horse, particularly the anesthetized horse,” Hazzard said.

The temperature of the pool today is maintained at 96o F. Since those early days of trial and error, numerous improvements have been made in multiple areas: a better raft, a better sling, better pharmacologic agents, and recognition that success requires a trained team of people.

New Bolton Center Builds a Pool

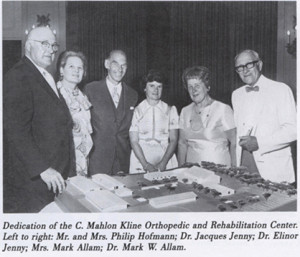

Construction on the C. Mahlon Kline Orthopedic and Rehabilitation building began in November 1971. The building – including surgical suites, the adjacent indoor anesthetic recovery pool, and a recovery barn – was completed in November 1972. Dr. E. James Roberts, who later became the first Jacques Jenny Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, oversaw the construction, due to Dr. Jenny’s poor health at the time.

The pool system was dedicated in 1975, featuring the pool measuring 22 feet wide and 11 feet deep; a custom-made life raft designed to accommodate a resting horse head and four horse legs; and a rail system making it possible to lift the horse from the surgical table, into the raft and the pool, out of the pool, and straight to a recovery stall.

The Pool Becomes an Important Tool

Use of the recovery pool was modest in the early years, until Dr. David Nunamaker’s arrival on the New Bolton Center campus in 1982. As a young instructor in orthopedic surgery, Dr. Nunamaker, a 1968 Penn Vet graduate, spent a year as a research fellow at the Swiss Research Institute’s Laboratory for Experimental Surgery in Davos, Switzerland. Dr. Nunamaker brought new enthusiasm as he used the pool for his patients. As his successes mounted, other surgeons gained confidence, and soon pool recoveries became more common.

Dr. Nunamaker remarked how some horses used the pool as many as a dozen times, as their conditions required multiple surgeries and cast changes. Being a true scientist/investigator, Dr. Nunamaker, along with operating room nurse Mary Ruth Hammond, maintained detailed records, allowing for future evaluation of the clinical outcomes.

Surgical resident Dr. Eileen Sullivan, working with Dr. Nunamaker, in 2002 published research on the outcomes of 393 horses that underwent recovery from general anesthesia in the pool-raft system.

Dr. Sullivan noted: “Horses are placed into the pool-raft system at the discretion of the surgeon, and criteria for selection are constantly evolving. For example, prior to the year 1987, horses with medial femoral condylar cyst lesions debrided via arthrotomy were routinely recovered in the pool-raft system because of concerns regarding disruption of wound closure. After 1987, arthroscopy became the standard treatment alleviating these concerns. A second example is prior to the year 1990, many horses with dorsal cortical metacarpal fractures were recovered in the pool-raft system. After 1990, standing surgery became the standard approach, eliminating the need for a modified anesthetic recovery.”

While there are several other equine hospitals with pool recovery systems today, they differ fundamentally from the New Bolton Center pool. In the other systems, the horse is partially submerged in the water and supported directly with a sling system. Because the horse and its newly operated limb are in the water, considerable care is required to keep the surgical site dry. In the New Bolton Center system, the horse’s body and limbs are within the rubber raft, which keeps the horse’s body dry.

Penn Vet’s pool was unique when conceived by Dr. Jenny, and remains unique today.

When asked if the pool recovery system made a difference in saving horses with catastrophic injuries that could not be saved otherwise, Dr. Nunamaker said, “Absolutely, that’s not even a question.”

FAST FACTS

Name: The C. Mahlon Kline Orthopedic and Rehabilitation indoor anesthetic recovery pool

Size: 22 ft. wide and 11 ft. deep

Volume: 30,000 gal of continuously filtered, brominated water

Temperature: 96°F

Special feature: A cantilevered deck surrounds the pool opening. This circumferential overhang allows personnel access to the horse while preventing the horse’s limbs from striking the pool wall during recovery.

Raft: A U.S. Navy 6-man life raft modified to accommodate 4 horse limbs.

Maintenance: When not in use, the recovery pool is covered with a solar cover to increase heating efficiency and minimize humidity.

Pool-Raft Recovery Protocol*

- The horse is sedated in the recovery stall.

- A large animal sling, suspended from an overhead monorail system, is loosely buckled around the horse in the standing position, and the horse is induced with injectable anesthetic.

- Following intubation, the horse is positioned on the operating table. After the surgery and related procedures are completed, the horse is lifted in the sling and lowered into the recovery raft.

- The sling and raft are on independent one-ton electric hoists, which can be transported to the recovery pool on an overhead monorail system 16 ft. above the floor.

- The horse and raft are then lowered into the pool, and the raft is secured to rings on the pool deck.

- Two ropes are used to control the horse’s head over an attached “tray,” a smaller flotation raft to support the horse’s head and prevent aspiration of pool water.

- A nasotracheal tube is placed, and oxygen supplementation is given at the discretion of the anesthetist, if the horse is not breathing spontaneously or if its respirations are shallow or infrequent while in the pool raft.

- The horse is sedated or tranquilized if it becomes anxious early in the pool recovery phase.

- Personnel observe the horse for increased periods of vigorous activity. The horse is transferred from the pool once it remains alert without transient periods of somnolence.

- A sedative is given before removal from the pool and transfer to the recovery stall, if the horse is excited.

- A blindfold is placed over the eyes and cotton in the ears to minimize patient stimulation.

- A minimum of six people is required to transfer a horse from the pool to a recovery stall.

- Staff working close to the horse during the process must wear protective headgear as an added safety measure.

- The horse is hoisted in the sling out of the raft and taken by monorail to the padded recovery stall. Ropes are attached to the sling to maintain position.

- The horse is lowered in the sling in a standing position until its feet contact the floor of the recovery stall. The blindfold is removed. Because the horse is quite awake and aware, most often it will stand as soon as it feels its feet hit the floor.

- Head and tail ropes assist the horse and maintain its orientation in the stall.

- The horse is allowed a few minutes to look around and is encouraged verbally and manually to stand.

- Immediately after the horse bears weight fully, the sling is removed. The sling can be removed in less than 10-15 seconds.

- The horse is walked to its stall 5-10 minutes later.

*Use of a pool-raft system for recovery of horses from general anesthesia: 393 horses (1984–2000) Eileen K. Sullivan, DVM; Lin V. Klein, VMD, DACVA; Dean W. Richardson, DVM, DACVS; Michael W. Ross, DVM, DACVS; James A. Orsini, DVM, DACVS; David M. Nunamaker, VMD, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association: 2002;221:1014–1018