Ranch Horse Riding Fundamentals – Part 1

Click here to read the complete article

Article and Photos by Kristen Spinning

At Paint and Quarter Horse shows across the country, it’s hard to miss the fact that Ranch Riding classes, formerly known as Ranch Horse Pleasure, are drawing huge numbers. During its initial rollout, the class was disparaged by some as being “a water-downed version of Reining.” Others saw it as an injection of renewed vitality. Clearly, the explosive growth is fueled by one simple fact: exhibitors find it fun. Yet, there are still numerous misconceptions about Ranch Riding, leaving many exhibitors wondering how the class can be incorporated into their show schedule. To find out the what’s, why’s and how’s, The Equine Chronicle sought out a professional who’s right in the middle of all the excitement.

At Paint and Quarter Horse shows across the country, it’s hard to miss the fact that Ranch Riding classes, formerly known as Ranch Horse Pleasure, are drawing huge numbers. During its initial rollout, the class was disparaged by some as being “a water-downed version of Reining.” Others saw it as an injection of renewed vitality. Clearly, the explosive growth is fueled by one simple fact: exhibitors find it fun. Yet, there are still numerous misconceptions about Ranch Riding, leaving many exhibitors wondering how the class can be incorporated into their show schedule. To find out the what’s, why’s and how’s, The Equine Chronicle sought out a professional who’s right in the middle of all the excitement.

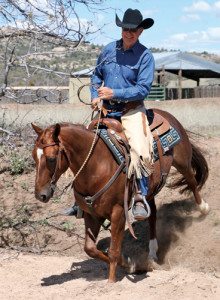

Laurel Walker-Denton was riding ranch horses before Ranch Riding was cool. It was a way of life while growing up on her family’s expansive cattle, Quarter Horse, and racehorse operation in central Arizona. Laurel showed in AQHA competition as a youth, competing in “everything but roping,” she says with a wistful twinkle. “The only reason I didn’t rope was because my mother thought a lady should have all her fingers.” Fingers still intact, many years later, Laurel is busily traveling the country showing, judging, and giving Ranch Riding clinics.

We caught up with Laurel and her husband, Barry, at their home on the ranch where she grew up. The Bar U Bar rolls across a serene, out-of-the-way valley. It’s a slice of Old West history that urban sprawl and cell phone towers have bypassed. One can immediately see that every bit of a Ranch Riding pattern is firmly tethered to its roots at this and similar ranches across the country. “The class is like coming home for me,” Laurel says. “It takes us back to the fundamentals of horsemanship. It puts the horse first, with a foundation of natural movement.” Laurel is passionate about increasing involvement in this deceptively simple, yet addictively challenging class. “It has brought out the most enthusiasm in the industry that I’ve seen in 40 years.”

There we were, at an old ranch, discussing the subtleties of a new class, based on the practical needs of an old ranch. Showing has made a grand circle to be sure. However, that circle is far from complete. Breeding and specialized training has been the norm for so many years that a Western Pleasure horse and a Ranch Riding horse are two entirely different animals. In fact, both APHA and AQHA rules state that a horse cannot be shown in both Western Pleasure and Ranch Riding at the same show. The training, movement, collection, and build of today’s Western Pleasure horse make it a pretty poor candidate for a serious Ranch Riding competitor.

From the rider’s perspective, there are major differences as well. It takes an entirely different mindset to successfully transition from rail classes to Ranch Riding. While Horsemanship, Western Riding, and Western Pleasure are all about collection and control, Ranch Riding is about moving with purpose and getting out of the horse’s way. Its circles might remind you of Reining, it has the lead changes of Western Riding, and the turns and precise maneuvers of a Horsemanship class. Yet it is much more than just a pattern class. The intention behind the maneuvers is not to exhibit how well you can control the horse. Your job as a rider is to show how well the horse can take care of himself, take care of you, and get the job done. The APHA Ranch Horse Trail, and soon to be unveiled AQHA Ranch Trail, share that “get it done” foundation. They might look like typical Trail patterns simply dressed up with brush and logs. In fact, some of the maneuvers of backing and turning between the logs or opening gates look very similar. However, the difference lies in the execution, extension, and transitions. Additionally, there are some challenging elements, such as the log drag, that horse and rider must master in a calm, yet purposeful way.

Laurel highly values this discipline’s return to fundamentals for improving the horsemanship of all riders. A flash of her independent-minded ranch mentality emerges when she comments, “the nice thing is that you don’t need to have a trainer with you at every step. You can attend a clinic, and then go home and work on it.” She also enthusiastically encourages Select riders to try the class, because it has a low physical impact on the body. Also, she believes many other trainers are beginning to see the benefits that Ranch Riding gives their riders: they become better able to think on horseback. The clarity and decisiveness necessary for Ranch Riding crosses over to improve abilities in other disciplines. It builds solid, trusting relationships between horse and rider. It was time to get out and see exactly how one prepares for a Ranch Riding class with Laurel, Barry and their assistant trainer, Morgan Dick. The early morning sun ignited golden halos around the horses’ ears as we headed to the “far arena.” Just getting there required the Ranch Riding skills seen in classes: opening gates, stepping over brush-fringed logs, navigating down the bank of a wash, and bounding up the other side. Eager, attentive and alert, the horses stepped out lively and with purpose.

Breaking it Down To Basics

What to Look for in a Ranch Riding or Ranch Trail Prospect Good attitude, enthusiasm, and alertness are important characteristics for a Ranch Riding horse. Cow horses and reiners make excellent Ranch Riding mounts. Their build, breeding, and training are well-suited for the quick gait changes and maneuvers. Ranch classes open a new avenue for these types of horses that might not otherwise find themselves in the show pen. Looking at the industry-wide picture, Laurel says, “we have so many horses bred for a certain job, but they can’t all do it at a World Champion standard. The beauty of this class is that here is another job they are well-suited for. It’s creating a whole new market for these athletes.” It’s important to note that there is no “perfect type” for Ranch Riding. Laurel insists that judges need to judge the horse in front of them rather than fitting them into a box. For instance, the horse should carry his head and neck in a natural position, rather than an artificial, perfect line. One horse might have a naturally high-set neck and carry his head higher. He should not be penalized for it, so long as he gets the job done.

Natural Movement

Laurel drums into her students that Ranch Riding is all about natural movement; the movement must fit the horse. It’s a true form-to-function scenario. She looks for flowing and balanced strides where the front and hind ends are smoothly integrated. There should be natural tailset and head carriage. The objective in a gait extension is to lengthen stride, not merely increase the quickness of the gait. “You want forward movement you would be comfortable riding for ten hours,” she reasons. “As a judge, I want to see a horse visibly lengthen when he goes from a walk to an extended walk. I’m always looking at what’s going on underneath. How far are those hind legs reaching under to power him forward?” In addition, Laurel wants to see a horse moving as if it had somewhere to go, navigating a lot of ground with a capability and agility that keeps both horse and rider safe. During clinics, “I stress that you’re trying to present a picture of capability to the judge—anything you come across in the course of your day, you can handle.”

Transitions

“Ranch Riding has so many numerous and quickly-spaced transitions that you need to go fast, yet be precise and immediate,” Laurel says. “If you miss one, or take too many strides in making one transition, you will miss the next.” The execution of each transition is as important as the speed. To score well, “you have to be decisive in your actions. If you’re going from a lope to a walk, and you stop or trot in between, that’s a break of gait and will result in a penalty.”

The Walk

This gait seems simple, but it’s important to remember it’s often the first or the last thing a judge sees. “It needs to be very purposeful while remaining a four-beat gait. It’s not about how quick you can go.” The type of walk she describes as being “fakey fast” is not what you would see on a ranch, and won’t cut it in the class. She suggests a fun exercise to do with your friends is a walking race. Ideally, you would be working outside the arena, urging your horses to go as fast as they can while still maintaining a walk. The first one to break stride is the loser. Do this continually to build up stamina and good habits.

The Trot

Again, it isn’t about speed. Simply moving the legs faster isn’t going to get you anywhere on a judge’s scorecard. In an extended trot, the judge will be watching for that length of stride. For that +1 they evaluate how far under the rear legs reach. Is it a smooth ride? “It’s not too slow, but not too fast either,” she says. “It’s more important how the rider is sitting on the horse. If going fast makes you look bad, then slow it down a bit so you look more comfortable. If your horse has a nice trot, this is where you can really show him off. Sell it!”

Extension of Gait

During her clinics, Laurel has everyone measure their horse’s stride, first thing in the morning, and then again at the end of the day to see if there is improvement. This is a technique anyone can employ at home. Trot with extension in a straight line down a trackless section of the arena. Measure and record the distance that the hind foot’s impression in the dirt reaches ahead of the forefoot. If you do it with a group of friends, you will find that the fastest extended trot doesn’t always result in the longest stride.

Cues

To manage the rapid transitions, cues must be instantaneous and clearly defined. “When going from a walk to an extended trot, you have to hit it in three strides or less.” Laurel advises adding new cues to make it clear for the horse. “For that immediate extended trot, I stand up. That’s something I don’t do when asking for a regular trot.” Many patterns ask for an extended lope straight down the arena. To differentiate from a regular lope, she has an additional cue. “Again, I take the weight out of saddle. When I sit back down, the horse knows to immediately slow down.” She adds that a rider’s cues don’t have to be the ones she uses. “What works for you is fine, so long as you own it and use it consistently.”

Tack

Ranch style is devoid of bling, first and foremost, but there are some other important distinctions from rail to trail. Tack serves a purpose on a ranch, and Ranch Riding tack follows those conventions. “I always recommend a flank cinch and a breast collar. It’s not a rule… yet. Both serve a purpose. If you have to trot to the top of the mountain, you need to have a breast collar. If you have to rope a calf, you need a flank cinch. It’s imperative that your tack fit properly.” Laurel is amazed at how much time is spent at every clinic just adjusting tack. “People forget that someone else might have ridden in that saddle or used that bridle, and they never readjusted it.” She points out some common mistakes that she sees in clinics and the show ring. “Breast collars cannot be loose and dangling. They must be snug to the belly, but not tight.”

Walk or Trot Over Logs

Every horse’s stride is different. You need to practice at home with different spacing so you will instantly be able to read it at the show. “That will help you to decide whether you have to speed up through the logs or slow your horse down to get the stride right.” The logs may be irregularly shaped and unevenly spaced at a show, but there is a maneuver score for the obstacle that’s affected by the difficulty. The horse must keep forward momentum, which the rider can help by getting weight out of the saddle. Even a missed step or a log hit may get credit if the horse demonstrates he’s really trying. Laurel believes that we will soon be seeing unusual logs at the larger shows, so find some gnarly ones to practice with at home.

Side Passing

The best way to start side passing is by facing a fence and using two reins. The inside rein is the directional rein. Try to avoid tipping the head to the outside. Once side passing is done smoothly and straight, you can progress to side passing over a pole or log. “The tricky thing is that every horse’s center is different. For some, it’s right at your heel. For others, it’s a few inches forward or behind. Get to know your horse’s center and line it up right over the pole.” She reminds students that their job is to make it easy for the horse, so don’t get his feet too close to the pole on either side.

Log Pull in Ranch Trail

Introduce this maneuver in small, safe steps. Laurel first uses a broke horse to drag a log around to show a new horse what’s going to be asked of them. She cautions it’s important to use a large diameter rope about 12 feet long. Face the log while holding the rope in your right hand and slowly move the log so the horse can see it. When that’s mastered, use patience, and move off to the left in a small circle. Still, hold the rope so the horse doesn’t feel the pull. The next step is to take one dally around the horn and face the log. Back slowly and move sideways to feel the pull. Laurel says your horse must be comfortable with this process before dragging something behind him in order to avoid a wreck.

Get Out of The Arena

Laurel stresses the importance of riding outside of an arena — both for the horse’s mind and the rider’s. Practicing all gaits over uneven ground builds a sure-footedness that’s critical to riding on a ranch. She suggests finding an area that has some natural elements. “We like using some trees or bushes to trot or lope around,” she says. You can circle, cloverleaf, weave, back around, or stop between trees, rocks, brush piles or whatever you may find.